The Artist's Guide to Grant Writing

Your budget is the story

of your project told with

numbers.

I used to hate budgets. Even the word was ugly. Squat. Clipped. No fun whatsoever. A budget felt like a grapefruit diet, something that had to be done if I wanted to be svelte but which left me feeling deprived. I didnât want to record dollars in black and white; the numbers laid bare made me nervous.

When I was growing up, if my mother wanted to buy something expensive, like nice fabric to reupholster a couch, she bought it and then reminded me on the ride home: âDonât tell Marvin how much this cost.â He was my stepfather and might not approve. Once, on a visit with my real father in Manhattan, we were sipping lemonade at a café. From under the table he pulled a wad of cash and thrust it at me. âTake it, spending money,â he said like it would evaporate if I didnât hide it quickly. I snatched it from him and jammed it in my jeans pocket. Why was the money a secret?

No wonder I didnât want to put numbers in black and white. I grew up believing that money, either expenses or income, must never be recorded in the open air for everyone to see. If you really wanted something it was best to hide how much it cost. And never divulge where your money was coming from.

Thereâs got to be internal consistency between the narrative and the budget so that Iâm reading the same story twice. Nothing should come up in the narrative that isnât echoed in the budget and vice versa. Budgets are the Achillesâ heel of many a grant writer in the arts. But remember, thereâs a staff at most granting agencies whose job it is to help you.

· KEN MAY, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, SOUTH CAROLINA

ARTS COMMISSION ·

When I grew up and started applying for grants, I was forced to make some budgets. I was shocked to discover that all my preconceptions about them proved wrong. Although creating a budget made me shaky, once I had one, I felt grounded and secureâhappy even. Announcing the numbers in black and white eased my anxiety. I wasnât dealing with some amorphous amount of money but rather a concrete number I could see. And having that specific number forced me to be creative about ways to find the funds. Numbers gave me the backbone to negotiate and ask for discounts, trades, and donations.

Despite all of this positive reinforcement, I still resist making budgets. Sometimes Iâm afraid to acknowledge how much my artistic projects really cost to make and how much money I need to make them. But at least now I realize that my resistance to budgets has less to do with mathematics and more to do with exposing my own desire.

Most grant applications require a budget. Your funder wants to know how you plan to spend the money.

Start making your budget early in the application process. Like the rest of your application, budgetsâeven small onesâtake time to make. You need to consider all your expenses, find out which expenses your funder does and doesnât cover, and research how much materials and services cost so that your numbers are accurate. A well-done budget demonstrates your experience and professionalism. Youâll need your budget, maybe even love your budgetâugly word and all.

Flesh Out the Numbers

Your budget comprises two lists: expenses (the money you want to spend) and income (the money youâll earn) for your proposed project. Together, these two lists tell the story of your project with numbers.

If you are applying for a small grant, your budget will be fairly simple. For example, if you propose a professional development grant to attend a workshop, then your expenses might be tuition, plane fare, and hotel. If you are applying for a project grant, your list of expenses will be longer. It might include artist fees for paying yourself and your team of collaborators, materials and supplies, equipment rental, airfare, studio rental, advertising, and so on. Your income would include any funds received from other grants, donations from individuals, in-kind donations, and your own money.

Helen Daltoso, a grants officer at the Regional Arts and Culture Council in Portland, Oregon, advises artists to make a budget even before they begin writing about the project. The exercise of making a budget helps you figure out exactly what your project will involve.

Visual artist Dread Scott used to struggle with budgets, but âNow itâs kind of easy,â he said. âIâm just figuring out what I needâhow much film? how much hard drive? Do I need to buy a new camera or microphone? Do I need airfare? Do I need to rent a car? I compare the income section with the expenses and I might end up with a $5,000 or a $30,000 hole â¦Â that has to be filled by a foundation or something,â he said. âBut the hole doesnât go away. I donât say, well, I canât see how to get the money so Iâll do the project with less.â

A well-done budget is specific and fully fleshed out. Because of the necessary detail, donât wait until the last minute to create one. If numbers scare you, make these lists with help from one of your team members. She can interview you about your project and write down all the possible expenses. Then, she can brainstorm with you all the ways you can earn money.

A well-done budget is specific and fully fleshed out.

If you have been running a successful art business, budgets may be no big deal for you. However, if art as a business is a new concept for you, making a budget for this one grant application will be great practice for all the budgets youâll need to make from now on in your career.

Expenses List

To create your budget, first list all the steps it will take to complete your project. Start at the very beginning and include every baby step. Take your time, and plan to work on several drafts of this document so that you donât forget any steps. Then write down every item that youâll need to purchaseâsuch as art supplies, printing services, travel expenses, marketing materialsâand everyone you want to hire to help you create the project, such as website designers or consultants. Do not concern yourself with costs for this first draft.

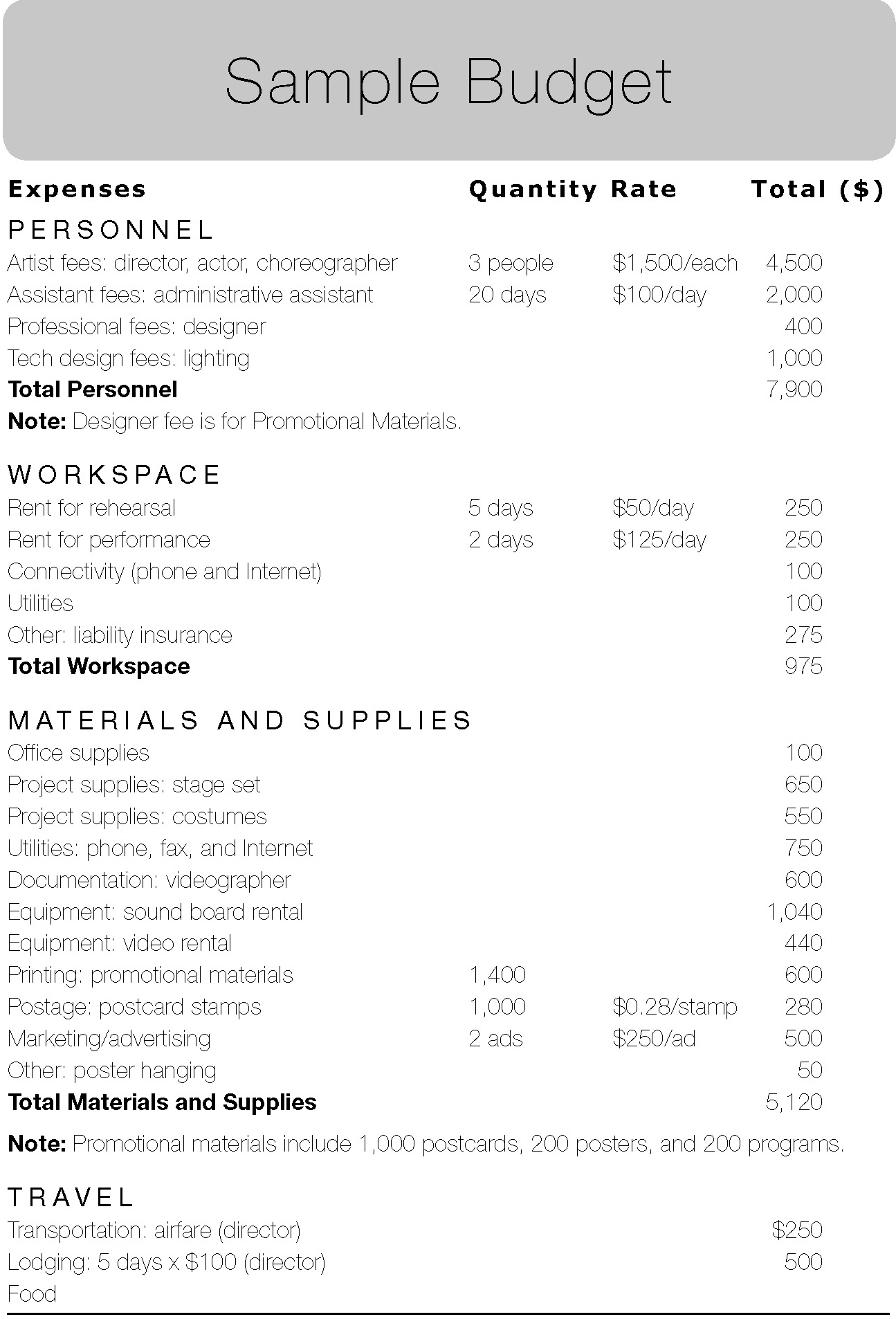

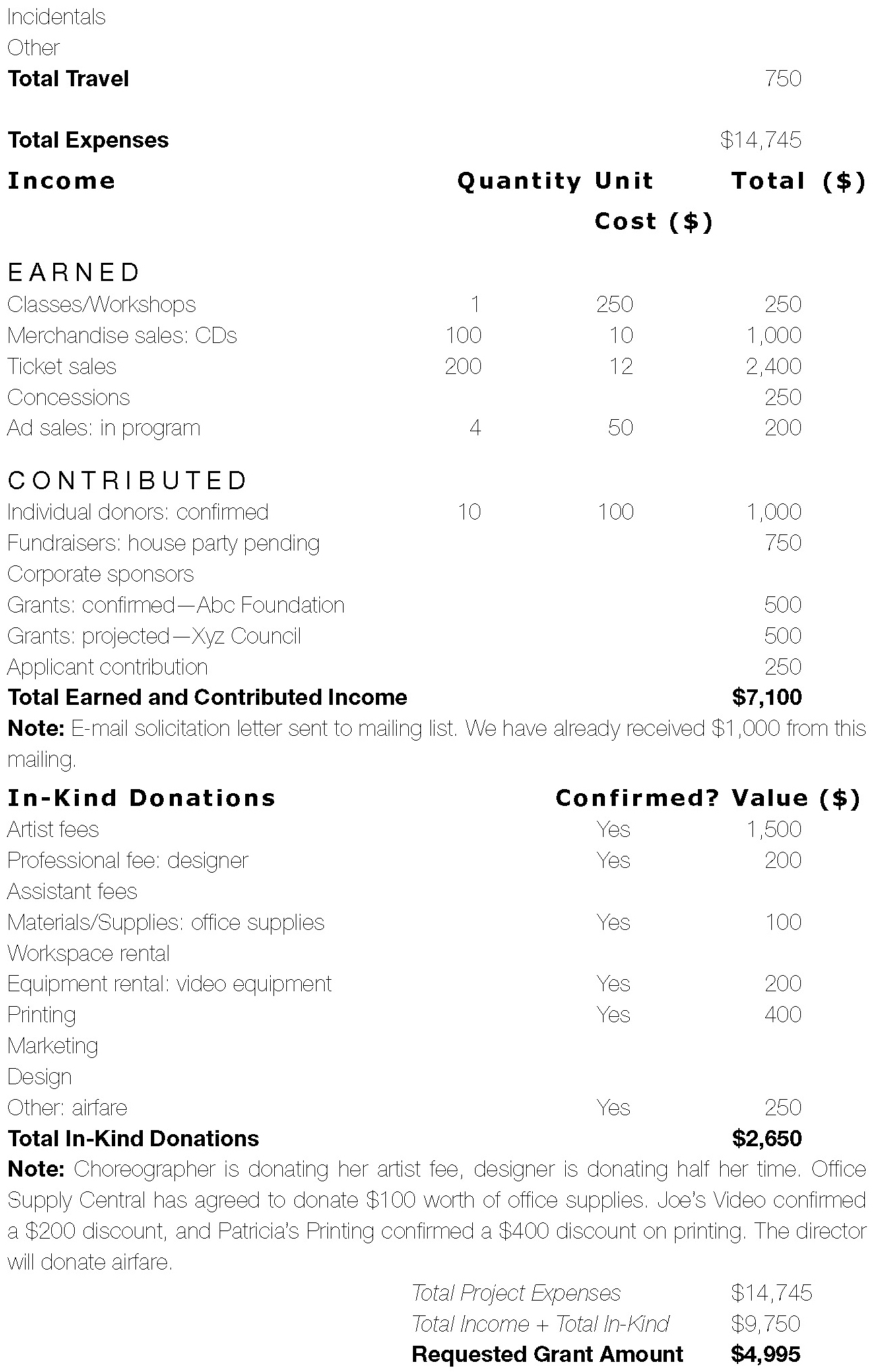

The sample budget (this page) lists many of the categories of expenses you may have on any project. Refer to it while you prepare your list of expenses to remind you of all relevant expenses for your proposed project.

RESEARCH COSTS · When your list of expenses is complete, write estimated costs next to each item. Some costs youâll know off the top of your head; others youâll have to research. How much is round-trip airfare to Iceland these days? What is the cost of printing 1,000 postcards? What is a graphic designerâs hourly rate? How much does canvas go for?

Depending on the detail of your budget, this step could take several hours and many drafts to complete. Most of the information can be found on the Internet or from your suppliers. You donât need the numbers to be accurate to the penny.

ESTIMATE LABOR COSTS · You may need to hire assistants, collaborators, web designers, photographers. List their fees at the going rate, and estimate their total fees on the basis of the numbers of hours and the hourly rates.

Daltoso urges artists to be detailed with their budgets so she can understand the design and planning of the project. In a budget, itâs almost impossible to provide too much detail. âIf thereâs a line item for artistic fees and somebody tells me the artist fees for two people are $1,000, well, I can extrapolate that thatâs probably $500 per person. But Iâd much rather know that one of the people is the director and the other person is a lead actor and that the director is going to get $600 and so on.â The details in your budget demonstrate how thoroughly youâve planned every aspect of your project.

YOUR OWN TIME · Most artists are stumped when it comes to estimating the cost of their own time because many feel like theyâre never paid or paid very little. However, grantors expect artists to be paid for their time, and it looks unprofessional if youâre not planning to pay yourself and your artistic collaborators. You may decide later to donate your time and list this donation in the budget under in-kind services. For now, estimate your time and your creative fee.

How do you estimate your time? First, calculate about how much time your project will require. To do this, walk through the steps of producing your project and write down the number of hours or days it will take you to complete each step. Then, figure out an hourly or daily wage based on the going rate for what you do. Ask other artists what they charge or what they have listed as a rate on successful grant applications. You can also calculate your fee as a percentage of the total cost of the projectâusually 10%â25%, depending on the size of the budget.

You can ask the funder if they have guidelines for figuring your artist fee. If the funder is used to working with artists, theyâll know that coming up with an artistâs fee is often a conundrum and will advise you on how other successful applicants have figured out the cost of their time.

Income List

If youâve ever made a household budget for yourself, you know that one of the key elements of any budget is incomeâhow much money you earn, perhaps in a few different ways. This number helps you decide whether youâll be eating rice and beans or Kobe steaks and Portobello mushrooms.

Make a list of all the possible ways you can earn money for your project. Think big. With your team, brainstorm every possible avenue for generating income. Consult chapter 11 for even more fundraising ideas. Your income list might include money that youâll raise from individual donors at events or through a direct mail campaign, merchandise that you will sell at your event, and some of your own money. Your income list should also include grants youâve received or intend to apply for.

Generating your income list will require some research and estimation. For example, if you plan to sell tickets to your event, you first will need to determine a ticket price. You may research what similar events charge or base it on what you charged last time for a similar event. Next, estimate attendanceâand always underestimate. If youâve put on this type of event before, then youâll know how many people showed up last time, which will help you estimate how many people will show up next time. Increase this number only if you plan on doing more marketing this time.

Make your estimates conservative. If youâre an emerging artist whoâs still building an audience, it will be unrealistic to expect to sell out for six weeks at Lincoln Center, for example. Overestimating attendance will make your proposal look amateurish.

Other Ways to Earn Income

Consider all of the ways in which your project can earn money, including the following.

Merchandise. Will you be selling anything (CDs, books, T-shirts, and so on) at your event? If so, how much do you estimate youâll earn from these sales? If youâve sold merchandise before at a similar event, then estimate how much you would sell at this future event on the basis of past sales. If youâve never sold anything, be conservative with your estimate.

Individual donors. The review panel will be impressed by your grant proposal if you already have the support of other people. Throw a fundraising party, and list the cash you receive as a donation on your income list. The more money you raise, the more competitive your proposal becomes. See chapter 11 for more ideas.

In-kind donations. In-kind donations are donations (or discounts) of goods or services that you otherwise would have to pay for. In-kind donations are almost as impressive as cash on a grant application because they show that individuals and business owners believe in your work enough to donate their time or products to help you succeed. Examples of in-kind donations include a program for your event from a printer and time to design your marketing materials from a graphic designer. The more donations you have, the more competitive your grant proposal will be, so get creative about all the items or services you could request from donors. From each person (or company) who promises an in-kind donation, get the commitment in writing, in the form of a signed letter. You may need to submit this letter with your grant application. But even if you donât, it will show that your donor is serious about the donation and clarify the agreement for both of you.

Other grants. A project always looks more competitive if youâve already raised money through another grant. List grants youâve already received as âconfirmedâ or âcommitted.â List grants youâve applied for and are still waiting on as âpendingâ or âprojected.â You can even list grants you plan to apply for in this last category.

Add It Up

Add all the items in the expense list to arrive at total expenses; add all the items in the income list to arrive at total income. Subtract the income from your expenses. The remaining amount should equal the amount of the grant youâre requesting. If this is confusing, see the sample budget (this page).

To make the numbers work you may need to lower some of your expenses (can any materials be obtained more cheaply, or can you do without?) and earn more income (can you throw another fundraising party?). You may have to adjust these numbers (along with your plans) several times.

Guidelines for Creating a Better Budget

After youâve created your income and expenses lists, the following tips will help you create a clear, clean, error-free budget to submit with your application.

EXPLAIN ALL LINE ITEMS · Label every line item completely. Relate each one to the expenses outlined in your proposal; none should be mysterious. For example, rather than âPrinting,â list âPrinting posters and postcardsâ and be sure that posters and postcards are discussed in the marketing section of your application. (Read the âKnow Your Target Audienceâ section in chapter 4, this page.)

Everything you mention in the application must also appear in your budget. For example, if youâve mentioned mailing invitations via snail mail, your budget must reflect the costs of printing invitations and postage. If youâve listed the cost of hiring a videographer in the budget, make sure that youâve described elsewhere on your application what the video will be used for. Will it document the project for future reference, or is it part of the artistry of the project?

CHECK THE MATH · Your budget totals must be correct. Always have another person double-check your math. Believe it or not, a miscalculated budget can disqualify your application. Typos in the budget matter.

TELL A COHERENT STORY · The budget has to make sense within the scope of the project. For example, if youâre planning a performance and estimating hundreds of attendees, your budget better list marketing expenses. It wonât make sense to expect a big crowd but not spend any money on getting them thereâunless you have already outlined a free, successful marketing plan in your proposal.

RECORD IN-KIND DONATIONS ON BOTH SIDES OF THE BUDGET · If you have arranged for an in-kind donation of goods or services, you must record it on both the expense and the income lists of your budget. For example, if your graphic designer is donating two hours of time at $50/hour, list âGraphic Designer 2 Hours @ $50 = $100â in the expenses and then list the same item under income.

REFLECT YOUR ATTITUDE IN THE BUDGET · The more income you can list in your budget and the better you show that you have thoroughly thought out every financial aspect of your project, the more impressed decision makers will be. Done right, your budget can reflect the attitude that youâre going to accomplish this project, no matter what. This attitude makes for winning applications.

Best case youâll have already won other grants for this project and collected cash from a fundraiser or two. Second-best, you have applied for other grants but havenât yet heard back and have several fundraisers planned with estimates of how much money youâll earn. Nobody likes to be the first one or the only one to finance a project. Contributors will be more excited if others before them have already donated. Individual donors and granting organizations like to give money to a project they know will succeed. Your attitude is what shows this.

Because chances are there wonât be adequate room on the budget form to list all your fundraising plans, mention any past fundraising successes and your commitments for future fundraising somewhere else on the application. If youâre unclear where this information belongs, check the guidelines or call the funder and ask.

CONFIRM ELIGIBLE EXPENSES · Make sure that all your budget items are for things that your grantor funds. For example, some grantors wonât pay for food or equipment purchases. Listing ineligible expenses will show that you didnât read the criteria and could disqualify your grant application. If youâre not sure if an item is eligible, read the guidelines. If youâre still unclear, call the funder and ask.

ASK TO SEE EXAMPLES · Some granting organizations let you review funded grant applications, including budgets. Study the budget for a similar project that was successful. If any information is confusing, ask the funder for clarification. Most funders are happy to help you finesse your application, especially when you ask them well in advance of the deadline.

NEVER ASSUME ANYTHING · If youâre unclear about what will and wonât make your grant application more competitive, call and ask the funder for guidelines. I once applied to the Oregon Arts Commission for a âcareer opportunity grantâ to attend the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop. Itâs usually best to have more than one source of income on your grant application, and I wanted my application to be competitive. I didnât have time to do any fundraising so decided to donate a couple hundred bucks of my own money and list it on the income list of my budget. After I received the grant, I found out that the commission didnât require applicants to list any income and would have paid the entire cost of my workshop. My donation was unnecessary. Now I know to ask.

Note: Consult a tax accountant after you win a grant. Unfortunately, youâll have to pay a percentage to Uncle Sam because grants are considered taxable income. Fortunately, the expenses you incur can usually be deducted from your income. Hire professional help so you comply with the rules, but donât pay more than you need to.

No Fake Budgets

One mistake many artists make in creating a budget for a grant application is starting with the maximum amount of the grant and working backward. They may see a grant for $6,000 and think, I want that money. So, they create an expenses list that adds up to $6,000. This is a fake budget because it doesnât start organically with the project and ask, âWhat will it take to produce this project?â Instead it starts with âWhat can I invent to get that money?â Funders can tell whether an application is for a project that is meaningful or a project that was invented to get some money.

Monica Miller spoke with many artists in the course of her job as former director of programs at Washingtonâs Artist Trust. Some artists who wanted grants invented projects that they thought would interest Artist Trust and make them eligible for funding, but the projects were not connected to the artistsâ work. âThe most important tip is for artists to stay true to their intentions and desires as artists and to reflect themselves in the application as much as possible,â said Miller. Once, an artist who wanted funds to hire a babysitter proposed a project that included âpublic critiquesâ of her work because she thought involving the public would appeal to Artist Trust. Part of her budget for the project included a line item for babysitting. When Miller asked the artist if her work was based on other peopleâs feedback, it was clear that it wasnât. This artist wasnât funded because the grant request didnât make sense; the project didnât relate to the artistâs work. She didnât propose a project she really wanted to do; she proposed a project she thought would appeal to the funder.

The way to create a real budget is to actually write down the expenses needed to produce your project in the fullest possible way. (In The Artistâs Guide: How to Make a Living Doing What You Love, Jackie Battenfield refers to this first pass as the âfairy godmother budgetââthe budget you would have in a perfect world.) Then write down all the funding you think you can raise. âThen you see whatâs left,â said Helen Daltoso, who reviews hundreds of budgets a year for professional development and project grants. âYou might really need $10,000. You might only need $4,000. In order to produce the clearest, truest, cleanest budget, you have to start at that place.â If it turns out that you need $10,000, then you can cut the expenses down to the essentials and build the income to get to $6,000.

A realistic budget will impress decision makers because it shows that you know what it takes to succeed.

When you start with your projectâs needs, itâs inevitable that youâll produce a true budget. This realistic budget will impress decision makers because it shows them that you know what it takes to succeed. A skimpy budget may make them wary about whether you can actually complete the project.

The Meaning of Money

Having money, wanting money, spending money, and especially asking for money can bring up your own beliefs, fears, and neuroses. Youâll be working on your grant application, and suddenly notice unexplained irritation, anger, shame, or feelings of entitlement. Why would anyone feel so strongly about recording some numbers? How could creating a budget inspire such spirited feelings to emerge?

Most likely youâre suffering the effects of doing something taboo: talking about money. Most people would rather discuss their sex lives than their personal finances. Money triggers emotions that have nothing to do with moolah. The sooner you uncover your feelings, the sooner you can sort through them and find your own clarity. Several books listed in Appendix C: Additional Resources to Support Your Career provide information on financial planning and help you sort out issues triggered by the green stuff.

Imagine your project finished. Itâs opening night, or the final day of the workshop you attended. What did it take you to get to this moment? Start at the beginning and list every baby step you took to arrive at where you are now. What did each step cost? Let the vision of your project lead you through developing your budget, then fill in the costs. Let the numbers ground you in reality. The best budgets are born out of your vision for what you want and need to create next.

- Donât scrimp on your first-pass list of expenses. Record the costs associated with your ideal project.

- Create you budget in tandem with writing the narrative of the application.

- Make sure that all items in your budget are mentioned in your answers on the grant application and vice versa.

- Record in-kind donations as both income and expenses.

- If working with numbers is difficult for you, enlist a team member to help you create your budget.

- Ask to see budgets from successfully funded projects that are similar to yours.

- Donât make a fake budget; create one that truly supports the project of your dreams.